Survival Architecture and the Art of Resilience

Section Four: RESILIENT

The ability to recover quickly from shocks and other adverse conditions is one definition of resilience, and it applies to communities as much as to people. Survival architecture helps show how providing stable and adaptive homes that can resettle displaced citizens can help communities rebound more quickly.

Nepal Earthquake

Thomas L. Kelly, 2015, photograph, 20 x 30 inches, © 2015, courtesy of Thomas L. Kelly

Kelly, an American photographer living in Kathmandu, Nepal, for the last three decades, lived through the 7.8 magnitude earthquake that rocked the country in 2015. He quickly began to document rural areas from both on the ground and from the air to show the devastation, portraying personal stories that testify to the reality of such tragedies.

Nepal Earthquake

Thomas L. Kelly, 2015, photograph, 20 x 30 inches, © 2015, courtesy of Thomas L. Kelly

In the words of Kelly’s son, Liam, “It is now time to work on building shelters, as monsoon season is quickly approaching. We must not let ourselves become daunted by the task of reconstruction ahead.”

Rebuilding Nepal: One Year On from the Earthquake that Devastated Nepal

Journeyman Pictures, 2016, still from video, 22 minutes and 25 seconds, © 2016, courtesy of Journeyman Pictures

Nepal was tragically unprepared for the 2015 earthquake. More than 8,000 people were killed in just minutes due primarily to poor construction practices.

With support coming from all over the world, there was hope that the rebuilding of Nepal would be different from past disasters, such as the poorly managed reconstruction of Haiti following its 2010 earthquake. Yet, Nepal’s displaced, living at the top of the world, have little choice but to rebuild with the same flawed designs and materials. For the post-Maoist government crippled by corruption and political turmoil over a divisive constitution, millions of dollars of aid lies unspent and not one home to date has been rebuilt by the government. The documentary Rebuilding Nepal: One Year On from the Earthquake that Devastated Nepal examines the country’s drive to rebuild both its fractured political system as well as its cities and buildings while looking to the future with hope and courage.

Palas por Pistolas

Pedro Reyes, 2008, shovels made from collected guns melted into steel, each shovel 161 x 22 x 14 cm, © 2008, courtesy of Pedro Reyes

This artistic intervention by the artist Pedro Reyes takes place in the botanical gardens in Culiacan, a Mexican city with a high death rate from gunfire. The community was asked to voluntarily donate their guns in exchange for a coupon, to be used to acquire appliances and electronics. Of the 1,527 weapons collected, 40% were military-caliber automatic weapons.

In a public act, the guns were crushed by a steamroller and melted at a foundry. The resulting metal was used to produce 1,527 shovels. The shovels have been distributed to art institutions and public schools, where adults and children used the shovels to plant 1,527 trees. This ritual shows how an agent of death can be transformed into a tool for life.

Zoom into the image to see additional photographs of the process.

Anthropod

Nathaniel Corum and Gerard Minakawa, 2016, bamboo splits and duck canvas, dimensions variable, © 2016, courtesy of Nathaniel Corum and Gerard Minakawa

Anthropod represents a range of solutions to post-disaster challenges, a flexible approach to self-built, open-sourced, humanitarian architecture. Collaborators Gerard Minakawa, founder and artist behindBamboo DNA, a small company specializing in large-scale architectural bamboo structures and environments, collaborated with Nathaniel Corum, an architect with Sustainable Native Communities Collaborative.

Their inspiration comes from working with natural materials, in this case, bamboo, the planet’s largest and most durable grass. As it happens, bamboo grows primarily in coastal, tropical areas, where communities are most vulnerable to hurricanes, earthquakes, and sea-level rise.

Fast-growing bamboo is an adaptable and renewable resource. Strong, light, and flexible, it is easy to handle and shape. The material allows even untrained people, in a matter of hours, to design and build structures that meet their needs and preferences.

Zoom into the image for additional views of Anthropod.

A Better Shelter

IKEA Foundation and UNHCR (UN Refugee Agency), 2013, photograph, 17 x 22 inches, © 2013, images courtesy of IKEA Foundation

Driven by a mission to improve the lives of persons displaced by armed conflicts and natural disasters, IKEA Foundation in partnership with the United Nations Commission on Human Rights created a safer, more dignified home for millions of people across the globe. Prior to the IKEA collaboration, UNCHR was able to provide only tents or converted mass-shelters for refugees.

The Better Shelter, created of lightweight plastic, comes flat-packed for easy transport. The 188-square-foot hut can be assembled in just four hours and has a life expectancy of three years. The structure has solar panels built into the roof, allowing inhabitants to generate their own electricity and extinguishing the need for candles or kerosene lamps. The roof also helps to deflect solar reflection by 70%, keeping the interior cool during the day and warmer at night. As of 2015, UNHCR had delivered 10,000 shelters to refugee communities.

Quinta Monroy, Chile

Alejandro Aravena, 2004, archival inkjet print, 17 x 22 inches, © 2004, courtesy of Alejandro Aravena

Chilean architect, Aravena, recipient of the 2016 Pritzker Prize — the highest accolade in architecture — is a visionary whose work gives economic opportunity to the less privileged, mitigates the effects of natural disasters, reduces energy consumption, and shows how architecture at its best can improve people’s lives. Aravena’s work reflects the architect challenged to serve greater social and humanitarian needs such as poverty, pollution, congestion, and segregation.

Aravena and his firm, Elemental, first came to international attention with a project that redefined the economics of social housing. “If there isn’t the money to build everyone a good house,” said Aravena, “why not build everyone half a good house — and let them finish the rest themselves.” Elemental’s Quinta Monroy housing in Chile provided a basic concrete frame, complete with a kitchen, bathroom, and roof, allowing families to fill in the gaps and stamp their own identity on their homes in the process.

Villa Verde, Chile

Alejandro Aravena, 2013, archival inkjet print, 17 x 22 inches, © 2013, courtesy of Alejandro Aravena

More recently, Elemental has released a number of residential designs, including Quinta Monroy and Villa Verde, as a free, open-source downloads to help tackle the global affordable housing crisis. The aim is to provide the material to governments and developers, encouraging and enabling them to invest in well-designed and affordable shelter.

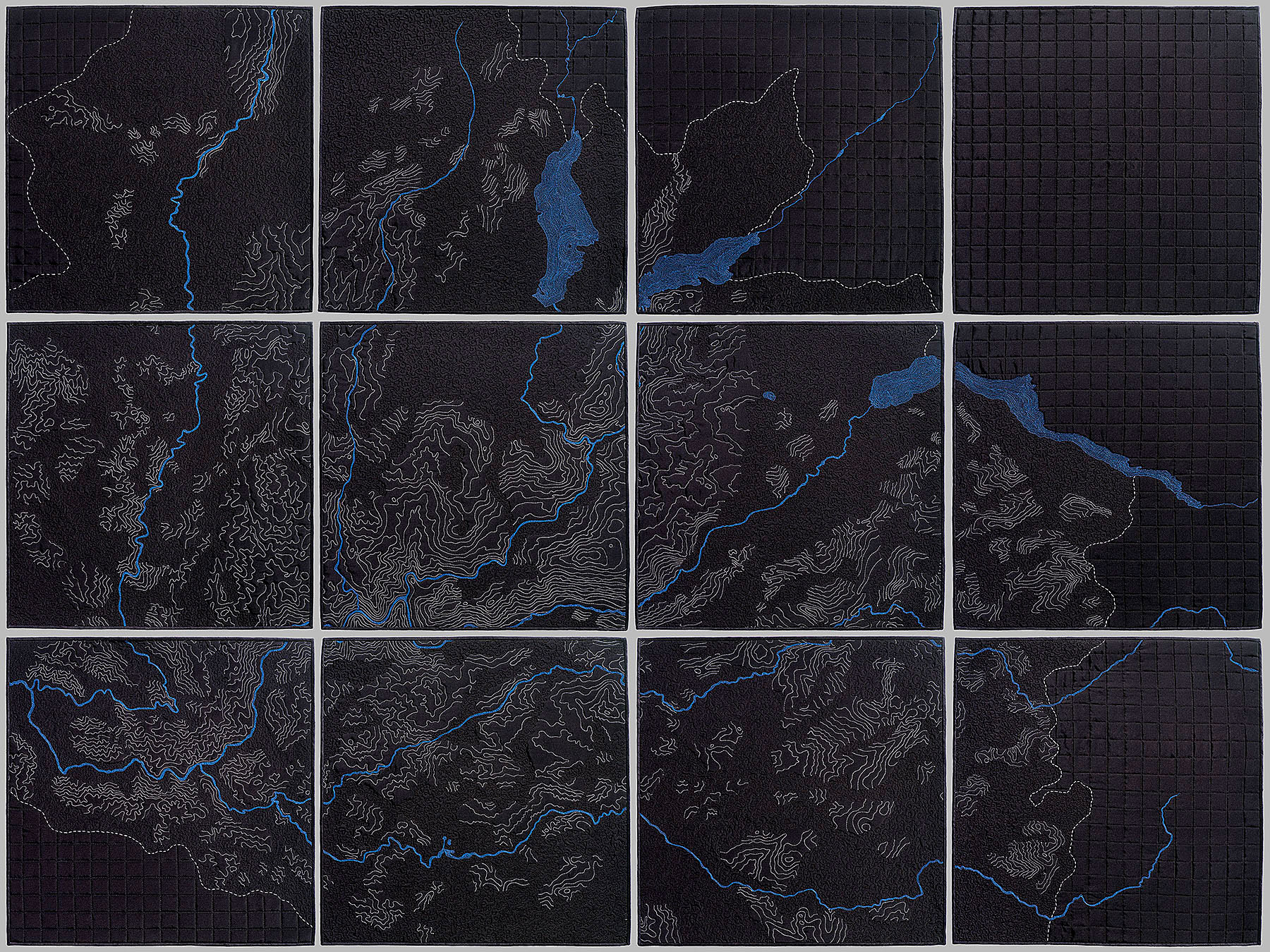

Severely Burned: Impact of the Rim Fire on the Tuolumne River Watershed

Linda Gass, 2014, stitched silk (silk crepe de chine, silk broadcloth, cotton batting, cotton and polyester thread), 54 x 70 x 1.5 inches, © 2014,

courtesy of Linda Gass. Photo: Don Tuttle.

The Tuolumne River Watershed provides 85% of the water used by 2.7 million residents of the San Francisco Bay Area. In 2013, 96% of the devastating Rim Fire burned in the Tuolumne River Watershed.

Fire is a natural and essential process in the forests of the Sierra Nevada. Centuries ago, wildfires burned slowly and low to the ground, thinning out excess brush and smaller trees, and leaving larger trees to thrive without competition for resources like water and sunlight. The 19th and 20th century policy of fire suppression to save forests and human lives resulted in the unintended consequence of allowing fast-burning fuel to build up in the form of dead and dry vegetation. Decades of well-meaning forest mismanagement coupled with the consequences of climate change in the form of drought and unusually high summer temperatures resulted in the mega-fire known as the Rim Fire.

In Severely Burned: Impact of the Rim Fire on the Tuolumne River Watershed, Gass overlaid the vegetation burn severity map from the Rim Fire on 7.5 minute topographic maps for the region and traced the topographic lines only in the areas that were severely burned. The Tuolumne River and its major tributaries and reservoirs are stitched in blue thread and the light grey stitched topographic lines represent the severely burned areas, highlighting just how much of the Tuolumne River watershed was reduced to nothing but ash.